What Does “Readily Converted” Mean for Firearms?

This is an in-depth legal discussion on what the term “readily converted” means with respect to firearm configurations.

This article is intended to help those who are interested in the nuances of defining this subjective term as it applies to the firearm industry.

If you are looking for a simpler approach, or are interested mostly in how the term applies to purchasing your own non-firearm for conversion into a firearm, please read my article on “80% Receivers.”

At what point during the manufacturing process is an object considered a firearm frame or receiver?

The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA), as codified in 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(3), defines the term “firearm” as:

(A) any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive;

(B) the frame or receiver of any such weapon;

(C) any firearm muffler or firearm silencer; or

(D) any destructive device.

It is clear in sub-section (A) above that a “weapon,” even one which is not able nor designed to fire a bullet, is still considered a firearm if it may be “readily converted” to do so. Therefore, the lowest threshold between what is and is not a firearm is not the ability to fire bullets but rather whether the “weapon” may be readily converted to do so.

Although the scope of what is considered a firearm extends beyond the present ability to perform an action and includes the potential future ability to perform that action after some modification, no similar treatment exists for determining what is or is not a frame or receiver. Sub-section (B) above provides that the frame or receiver of “any such ‘weapon’” described in sub-section (A) is a firearm. Therefore the completed frames or receivers of both “weapons” that shoot bullets and “weapons” that may be readily converted to shoot bullets are considered firearms. Therefore, one could argue that sub-section (B) of the definition of a firearm only includes objects which are currently frames or receivers since no statutory language exists which would include objects that could be frames or receivers in the future.

The “readily converted” standard only applies to “weapons.” According to the GCA, three types of “weapons” are firearms. They are those that will shoot bullets, those that are meant to shoot bullets, and those that can be “readily converted” to shoot bullets. It can be argued that if the starting object is not a “weapon,” it is irrelevant whether it may be readily converted to fire bullets. According to the GCA, only the frame or receiver of a “weapon” which may “readily be converted” to fire bullets is a firearm. There is no language addressing objects which may only be readily converted into a frames or receivers.

Since no language in the GCA helps to determine what is or is not a frame or receiver, it is necessary to look to the ATF’s implementing regulations in Chapter 27 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). ATF Regulations in 27 CFR § 478.11, which also share the GCA’s definition of firearm, define a “frame or receiver” as:

That part of a firearm which provides housing for the hammer, bolt or breechblock and firing mechanism, and which is usually threaded at its forward portion to receive the barrel.

Additionally, the Glossary of the Association of Firearm and Toolmark Examiners (2nd Ed. 1985), an international authority in firearm forensics, defines “receiver” as:

The basic unit of a firearm which houses the firing and breech mechanism and to which the barrel and stock are assembled.

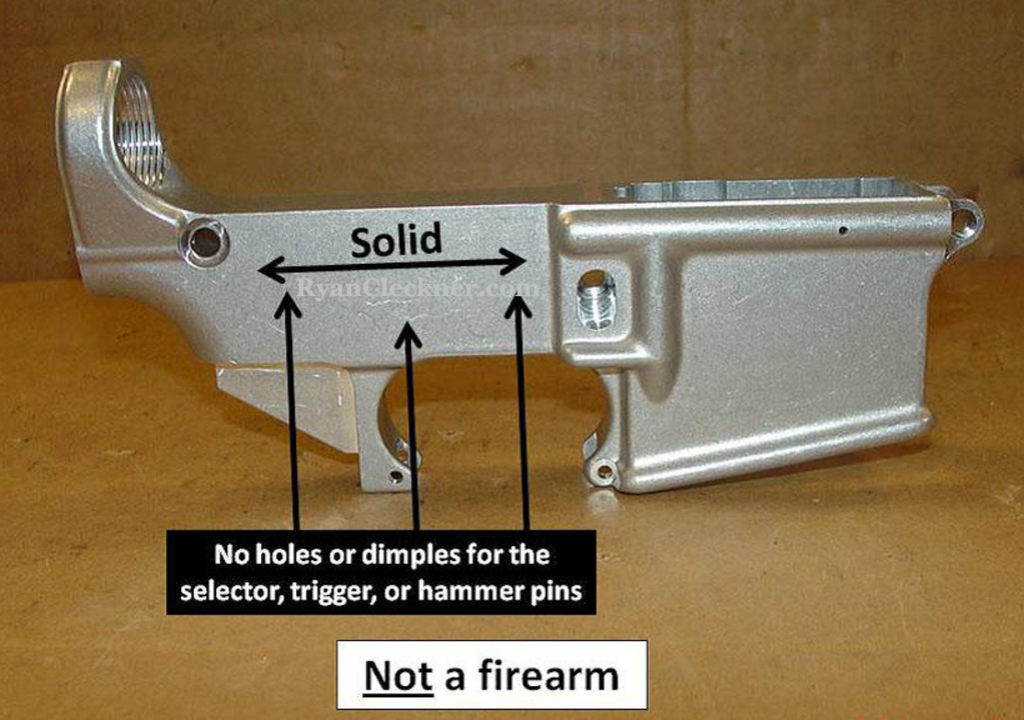

According to the above definitions, raw material is only considered a frame or receiver once it has been machined to accept (provide housing for) the firing mechanism. Therefore, regardless of whether the “readily converted” standard applies to what is a frame or receiver under sub-section (B) of the definition, if an object is unable to accept the firing mechanism, it is not a frame or receiver. This entire discussion may solely be academic because in my experience, the ATF has determined that objects are not “readily convertible” into firearms when no machining has been done to start the firing mechanism housing area of the future frame or receiver.

What Does “Readily” Mean?

No case law addresses when an object may be readily converted into a frame or receiver. And, no definition of “readily” exists within the GCA or ATF’s implementing regulations. However, case law concerning “readily” restoring semi-automatic firearms into fully automatic firearms does address the issue. And, since ATF also has statutory authority over fully automatic firearms through the National Firearms Act (NFA), it is prudent to look to various courts’ interpretations of “readily” restored with respect to the NFA for help in understanding what the definition of “readily” converted means.

The NFA, as codified in 26 U.S.C. § 5845(b), defines a machine gun (fully automatic firearm) as:

Any weapon which shoots, is designed to shoot, or can be readily restored to shoot, automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.

The test for what is considered a machinegun is very similar to the test for what is considered a firearm in that both definitions include not only items which perform in a certain way but also those items which may be “readily” modified to perform in that way. This is another indication that the “readily converted” standard does not apply to frames or receivers. If Congress had intended it to apply, it would have included the “readily” converted language just as it has for firearms and machine guns in multiple locations.

Just as the GCA does not define “readily converted,” the NFA does not define “readily restored.” However, the term “readily,” with respect to the NFA, has been read by courts to “encompass several elements of restoration: (1) time, i.e., how long it takes to restore the weapon; (2) ease, i.e., how difficult it is to restore the weapon; (3) expertise, i.e., what knowledge and skills are required to restore the weapon; (4) necessary equipment, i.e., what tools are required to restore the weapon; (5) availability, i.e., where additional parts are required, how easily they can be obtained; (6) expense, i.e., how much it costs to restore the weapon; (7) scope, i.e., the extent to which the weapon has been changed . . . ; (8) feasibility, i.e., whether the restoration would damage or destroy the weapon or cause it to malfunction.” United States v. one TRW Model M14, 7.62 Caliber Rifle from William K. Alverson, 441 F.3d 416 (6th Cir. 2006).

Despite determining elements of “readily” for consideration, no clear standard exists. Individual courts choose which elements to consider as well as how to weight each element’s importance. With varying interpretations from court to court and the absence of a clear standard defining “readily,” compliance with the law is difficult at best. For example, with respect to the element of time only, one court has determined “readily” to mean that the modification can be completed within two minutes. United States v. Woodlan, 527 F.2d 608 (6th Cir. 1976). This could lead someone to believe that modification which requires an hour to complete is not done so “readily.” However, another court focused on both time and equipment and said that a firearm was deemed “readily restored” even when it required an eight-hour working day in a properly equipped machine shop in order to be converted. United States v. Smith, 477 F.2d 399 (8th Cir. 1973). Depending on which standard is used, a seven hour and fifty-eight minute window of time and a complete disparity of the level of equipment needed exists between what is and is not a firearm.

Other courts have displayed similar discrepancy when determining “readiness.” Focusing on both time and equipment, the Alverson court defined “readily” as the ability to manufacture the required parts in four to six hours with particular machinery or in two to three hours by hand. Alverson at 423. Another court determined that a two-hour process that required only simple tools and a stick weld was enough to “readily” convert. United States v. TRW Rifle 7.62x51mm Caliber, One Model 14, 447 F.3d 686 (9th Cir. 2006).

One court ignored the elements of time, expertise and equipment and instead focused only on the availability of parts. The court declared that a disassembled weapon, which was missing a necessary part, was considered “readily restored” simply because the necessary part was available on the open market. United States v. Cook, No. 92-1467, 1993 WL 243823 (6th Cir. 1993). Another court set an extreme upper limit on what is not considered “readily” without helping to define what is. It can be assumed that anything less than what the court declared is not “readily” could be considered “readily.” In an extreme example, the court said that a firearm is not considered “readily” restorable when conversion would require an expert gunsmith with tools costing up to $65,000, working between “four and perhaps in excess of thirty hours,” using essential parts that can not be found in this country and doing modifications that could damage or destroy the firearm and cause injury to the shooter upon firing. United States v. Seven Misc. Firearms, 503 F.Supp. 565 (D.D.C. 1980).

A few courts have referred to the Smith “eight hours in a machine shop” standard when determining readiness. The Alverson court upheld a conviction of the defendant where six hours in a machine shop would have been required to modify the firearm. The court reasoned that since six hours was less than the eight hours standard from Smith, six hours of machine shop time was within the definition of “readily.” Another court denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss his indictment by relying on the Smith eight hour standard. The court said that the one hour of time that would have been required by the defendant was less than eight hours and therefore should have been considered “readily.” United States v. Catanzaro, 368 F.Supp 450 (D.Conn 1973). Even if the Smith determination was a standard which could be relied upon, a large problem would still exist. In today’s manufacturing world, machine shops can produce hundreds of firearms in an eight hour work day. Using the Smith standard, raw materials should be considered firearms a hundred times over.

How to Determine whether an Object is “Readily Convertible” into a Firearm

With these varying interpretations of “readily” from courts and no clear industry-wide definition from ATF, it is difficult to confidently know exactly when an object is “readily convertible” into a firearm. If you want to know if a particular object has crossed the line into becoming regulated as a firearm, then you should reach out to the Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division (FATD).

The FATD will analyze your sample and provide a determination to you about whether it is considered a firearm. In my experience working with them, they can also be relied upon for guidance on how to change the status if you are so inclined. Be careful relying upon determinations by FATD (formerly FTB) for other FFLs – each situation is unique and unless the guidance from the ATF has been given to the entire industry, then the specific guidance from ATF to one FFL is strictly for that FFL.

Recent Posts

July 26, 2024

July 26, 2024

July 25, 2024

![The Best Shooting Hearing Protection in 2024 [Tested]](https://gununiversity.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/best-shooting-hearing-protection.jpg)

Hi Ryan, were you prophetic about the raid on P80? Seems like the entire ATF case is based on their definition of the word “readily”. Sounds like now there are trying to argue it includes “machining” or at least “the use of power tools to precisely remove material”.